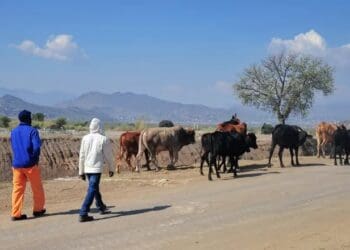

The image of commercial agriculture being the preserve of white men in safari suits is fast becoming a hazy memory.

Young black farmers are staking a claim in the field despite challenges ranging from access to land, start-up capital and breaking into markets long controlled by the big players.

Pfananani Augustine Nemasisi, known as Pan to his peers, operates from a plot in Rietvlei in Makhado, Limpopo. He was earning a living as a photographer in Pretoria when a friend planted the idea of tilling the soil in him. His parents were farming chickens on a plot in Makhado, the subtropical town dubbed the Gateway to Africa.

“Now I’m full time into farming with the whole land. That’s how I began farming,” he told Vutivi News.

“Before I became a farmer, I was a photographer and also a stylist. I would buy and resell the suits. That’s what I was doing before,” Nemasisi said.

Although raising start-up capital wasn’t much of a challenge given the support of his parents, he soon found out that to break into the market to sell his produce was a daunting task.

“I still remember when I started harvesting my cabbages. I took one of the biggest cabbages that I had on the farm. I went to the supermarkets showing them this is what I have on the farm and all of them are like this. I can supply them for you if need be.

“Some supermarkets told me to my face that no, we don’t need you. And painfully, when I checked what they had and what I was carrying, it was nothing compared to my product,” recalled Nemasisi, who is also a pastor.

This was the kind of response by big business that had seen young emerging farmers give up. But Nemasisi persevered.

“Eish, it was very slow and painful. I remember I will wake up early in the morning every day to go and stand at the hospital to sell cabbages. Sometimes we will sell, sometimes it will not be a good day at the office,” he says.

“So it took me long to be able to sell the cabbages and the mustards that I have but I did not give up,” he said.

His perseverance paid off and he was currently farming Florida broad-leaf, spinach mustard, cabbages and onions.

“I have the free-market that I sell to, and also the feeding scheme guys even though now we were hit hard by Covid – 19 because they were no longer supplying to the schools and also some of the big superstores around here,” Nemasisi explained.

READ MORE: Local tourism not for black people

During the Covid-19 lockdown the Department of Agriculture gave farmers like Nemasisi vouchers which they used to buy fertilisers and chemicals.

“So I think they have met us halfway, so a lot of things are easier for us to grow the cabbages and the mustards because of the supplied fertilisers and chemicals. I think for the whole year we will be covered,” he said.

He had three permanent employees before the Covid-19 but was forced to retrench one of them but he was hoping that with the passage of time he may be able to create more jobs.

Nemasisi advised his peers who were coming into the industry to be passionate.

“I don’t even have my own time so therefore if you are not passionate about it you cannot survive because you have to love what you do. For me to be able to wake up every day in the morning and be here, sometimes I leave here at eight [at night]. It takes passion, without passion, you cannot survive.”